Tree: Anatomy & identification

The true meaning of life is to plant trees, under whose shade you do not expect to sit.

Nelson Henderson

Introduction

- Introduction

- The redwood

- Uses

- Tree anatomy

- Deciduous tree leaf identification guide with drawings

- Deciduous tree leaf identification guide without drawings

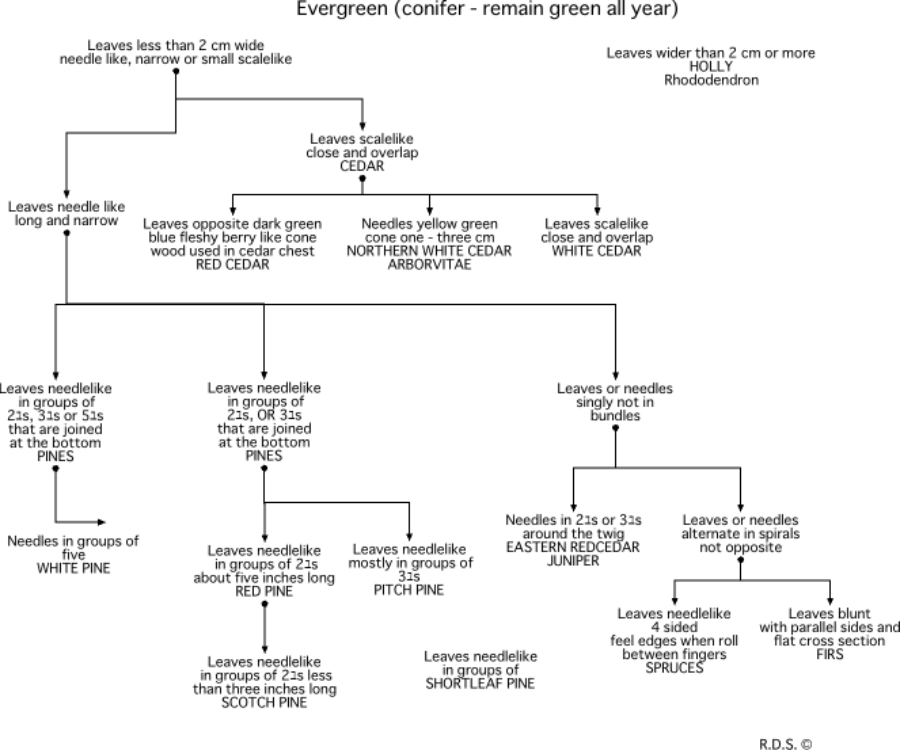

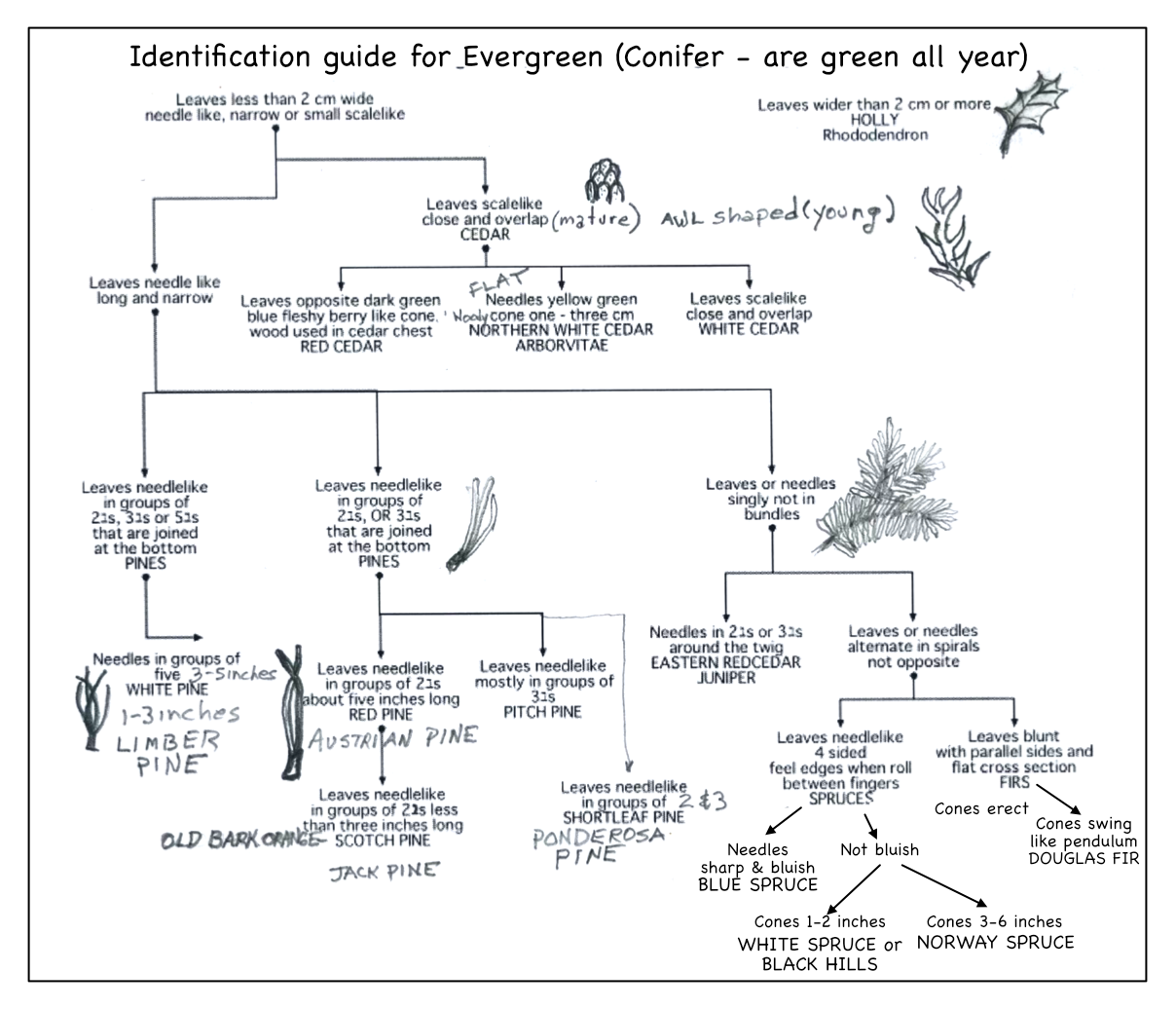

- Coniferous tree leaf identification guide with drawings

- Coniferous tree leaf identification guide without drawings

- Introduction to dichotomous keys

This page includes information about trees. Redwoods, tree anatomy: leaves, trunks, roots, uses and enemies. An introduction to twig anatomy and identification. And three sample dichotomous keys: 1. for leafy trees (deciduous) illustrated and not, 2. evergreen (conifer) trees illustrated and not, and 3. illustrated tree twig identification guide.

More information can be found with:

- Plants

- Tree rings primary

- Tree rings middle level

- Wood - what maks wood heavy? How does a seed becomes a big tree?

The Redwood

Redwoods evolved about 200 million years ago. They survived the splitting of Pangea, the Chicxulub asteroid that killed the dinosaurs, and many other natural disasters and climate changes.

They survived as they grew to be 350 feet tall and 30 feet in diameter and living for 3000 years. Topping as a 2 million acre forest along the coast of the U. S. From San Francisco to Oregon in the 1800’s. Today, less than 4% of the trees in the same area are redwoods.

Their decline began in the late 1800’s when private companies illegally acquired much of the lands and after World War I began to strip cut the forests and sell the lumber for the growing country’s infrastructure.

Later at the Bohemian Grove resort business titans hatched plans to create the Save the Redwoods League as a smoke screen to hide their plans to continue logging the majority of those left.

Source: The Ghost Forest: Racists, Radicals, and Real Estate in the California Redwoods. 2023.

Uses

Trees are important to humans for many reason, some are:

- Soil stability - stopping and slowing soil erosion,

- Controlling floods

- Create healthy watersheds to help to increase water supply

- Help break up rocks and make new soil

- Add organic matter to soil

- Provide shelter for animals

- Supply food: leaves, flowers, fruits, nuts, spices, for humans and for animals,

- Supply lumber, plywood, cork

- Made coal

- Supply oxygen

- Medicine: quinine

- Provide paper, cardboard

- Provide dyes, tanning material

- Provide rosin, turpentine

- Aesthetic- good to look at and walk under, and sit under

- Help build up land along rivers and swampsn and mangrove trees

Tree anatomy

The crown of the tree has the small branches, twigs, leaves, flowers, and fruit.

Leaves

Leaves are the part of the tree where most of the photosynthesis takes place. This is the process where the plant uses energy from the sun, water, and carbon dioxide to make food (glucose). In the process it gives off oxygen. Plants are our major source of oxygen.

Parts of the leaf include the: upper epidermis, pallisade cells, veins, spongy parenchyma, lower epidermis and stomata. These are labeled and described on the cross section of the leaf.

Leaves are different on different types of trees. There are three classes of trees:

- Pteridophytes - tree ferns,

- Gymnosperms - conifers (evergreens); ginko; maidenhair; cycds,

- Angiosperms (flowering trees) - maple; ash; oak; yuccas, palms, aloes, walnut; elm; and cottonwood. The angiosperms are further divided into two more divisions:

- Monocotyledons -include palms; yuccas; aloes, and

- Dicotyledons - include apples, birch, elm, maple, oak, poplar, willow, and walnut.

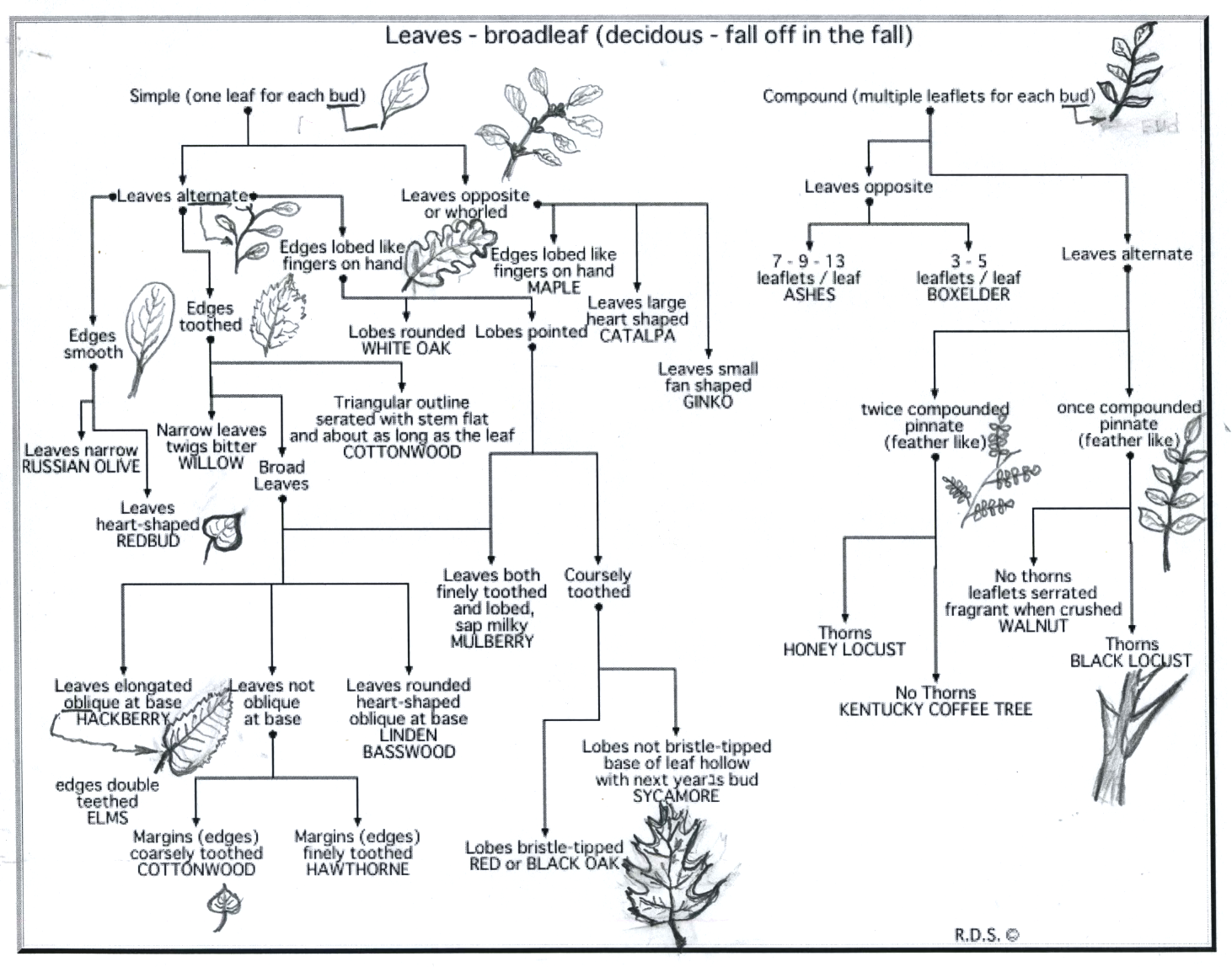

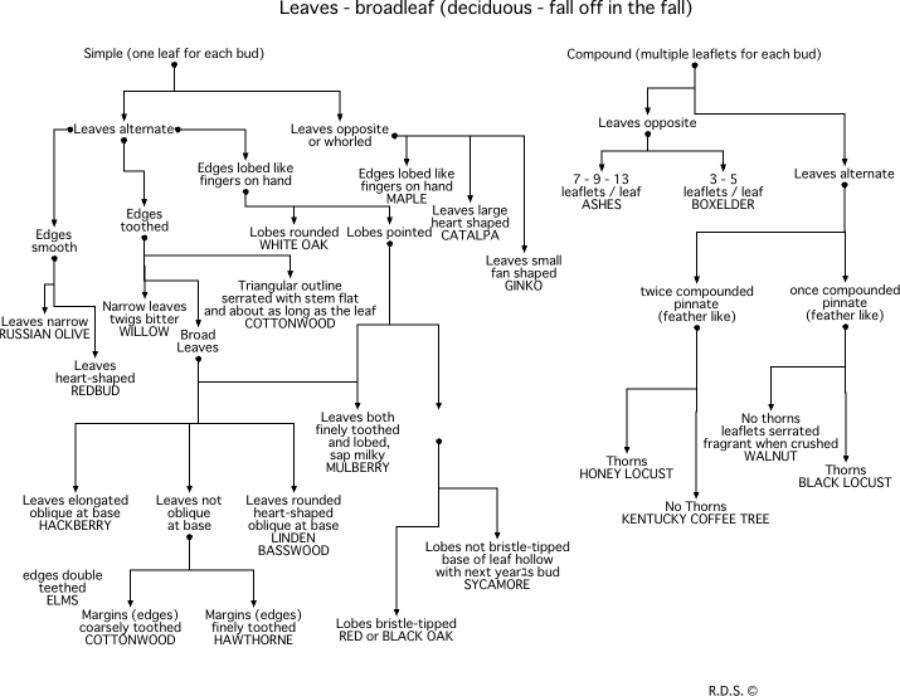

Leaves are one of the most common ways to identify trees (see leaf identification guides).

Leaves are arranged as simple or compound. Look for the bud or the bud scar to tell which the leaf is. Types of simple leaves are maple, oak, cottonwood, elm, and apple. Examples of compound leaves are locust, ash, sumac, and walnut.

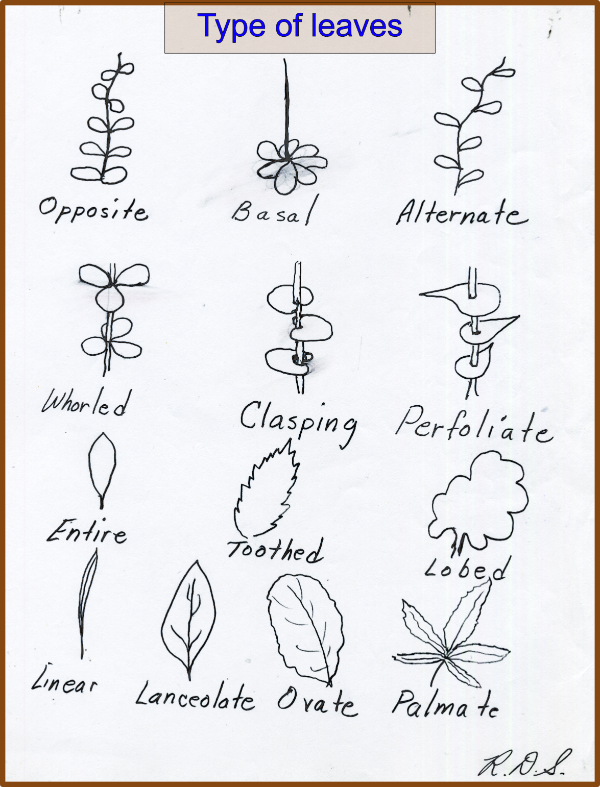

After determining if the leaf is simple or compound (see diagram on leaf identification guide), another step in identification is to determine how the leaves are arranged on the stem. They may be opposite, basal, alternate, whorled, clasping, or perfoliate. Example are shown in the diagram.

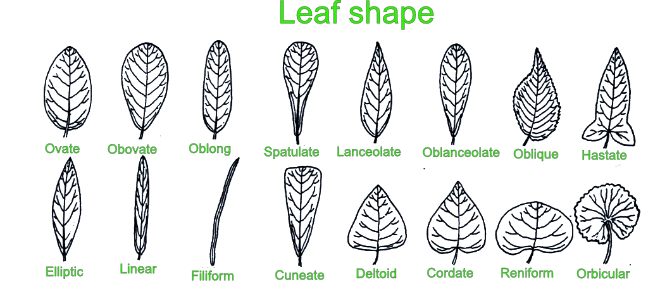

Leaf shape

The edges of the leaves are also noted for identification as: smooth, wavy, serrate, double serrate and lobed.

The shape of the leaf itself is also used in identification. Some examples: linear, lanceolate, ovate, palmate, triangular, diamond, and heart shaped.

Finally the surfaces may, also be used, such as, smooth or rough (slippery elm).

Leaf types

Flowers

Flowers, remember that angiosperms (flowering plants) have flowers.

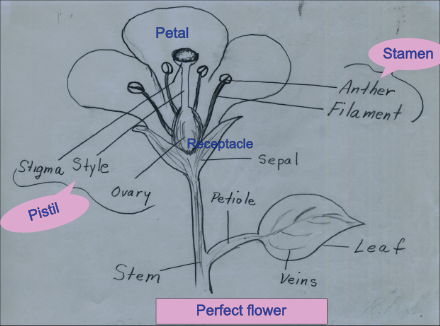

The main parts of the flowers are: pistil - stigma, style, ovary; stamen - anther, filament; and petal.

Not all trees have flowers with all of the parts: sepal, receptacle, and stem. However, if a flower does have all these parts, it is said to be perfect.

Some flowers are just pollen bearing flowers and are called staminate (stamen) others are just seed producing flowers and are called pistillate (pistil).

Gymnosperms (naked seed) since there is no pistil in the conifers, the seed producing flowers are not pistillate, but ovulate. Look at an evergreen tree in the spring to see these flowers.

Coniferous fruit (evergreen) may be either dry (cones) or fleshy. Dry seeds are usually born on scales around a central axis to form à cone. Others covered by a pulpy material are called an aril.

Angiosperms fruits are also either dry or fleshy. Dry fruits that split open along a line are: legumes: they split along two lines, follicle splits along one line, and capsule splits along several lines. Fruits that lack such lines fall into other categories.

- Achene are small unwinged but plumed fruit like the sycamore.

- Samara are winged fruit like the maple helicopters.

- Nut like oak.

- Pome with an inner wall of tough papery material encasing numerous seeds like an apple.

- Drupe fruit with one seed and fleshy fruit like peach, hackberry and cherry.

- Berry has several seeds embedded in a pulpy mass

Tree trunks

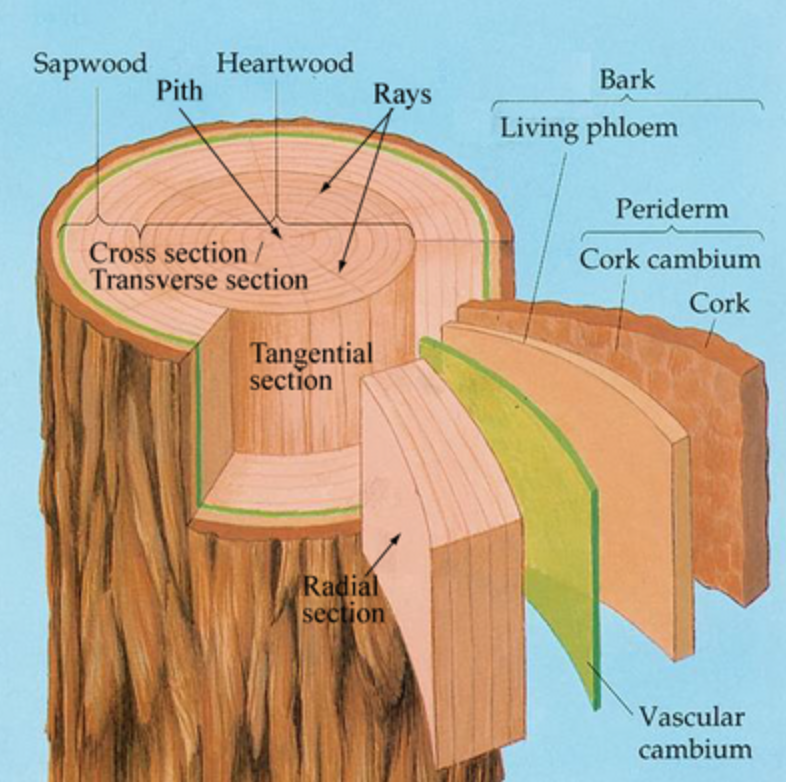

Trunk or stem. If the trunk or stem is cut cross wise the following areas may be seen.

- Pith is the central region of the wood is the pith. It is surrounded by other regions of wood (cambium) and then both are enclosed by the bark.

- Cambium is between the bark and the wood it is the area where the tree grows. This growth is the adding of new cells to the region outside the wood and just inside the bark.

- Bark. Each year a new layer of wood is added and a new layer of bark is added under the old bark. This makes the outer bark stretch and gives it its appearance. It is this growth that also gives the tree its rings.

- Wood - what maks wood heavy? How does a seed becomes a big tree?

The study of tree rings is known as dendrochronology and is used to look back in time to see what the weather and climate was before records were kept. In the southwest United States this has been done so we have a record of tree rings that overlap one another and have been pieced together to go back thousands of years.

The study of tree rings is known as dendrochronology and is used to look back in time to see what the weather and climate was before records were kept. In the southwest United States this has been done so we have a record of tree rings that overlap one another and have been pieced together to go back thousands of years.

The rate of growth is measured in tree rings per inch 3-5 rings or less per inch is considered rapid growth, 8-10 rings per inch is medium growth, and more rings per inch is considered slow growth.

The cambium, a one cell layer between the phloem and xylem, it is the growth area and needs to be provided with materials to grow. To move the materials around the tree there are two types of vessels.

- Xylem, which caries the water and minerals from the beters roots to the leaves and

- Phloem which carries the food manufactured in the leaves to the roots (except in spring).

When the storage gets crowded in the leaves and roots, it will then store in the wood, fruit, and seeds.

Passage of food from these vessels to the wood is done in the medulary rays. You can look at leaf and twig scars and see evidence of these vessels.

As the tree ages the center wood becomes darker, as a result of the food stored in this region. It is called heart wood and is what adds color to wood and makes it more valuable.

See also twigs

See activities: Tree growth 3rd grade+, Tree Rings middle level, and measuring trees.

Roots

Roots are used to hold the tree in place, for the gathering of water and soluable materials from the soil, and the storage of food. The tree may have a tap root, lateral root, branching roots, and root hairs.

Types of trees:

- Seedling, from seed till sapling.

- Sapling (all measuring is done from four and one half feet off the ground) measures 2-4 inches diameter.

- Pole is 4-8 or 12 inches diameter.

- All larger trees are saw timber or mature.

Enemies of trees. Lightning, fire, wind, ice, insects, disease, wild animals, polluted air, polluted soil, drought, flooding, and humans.

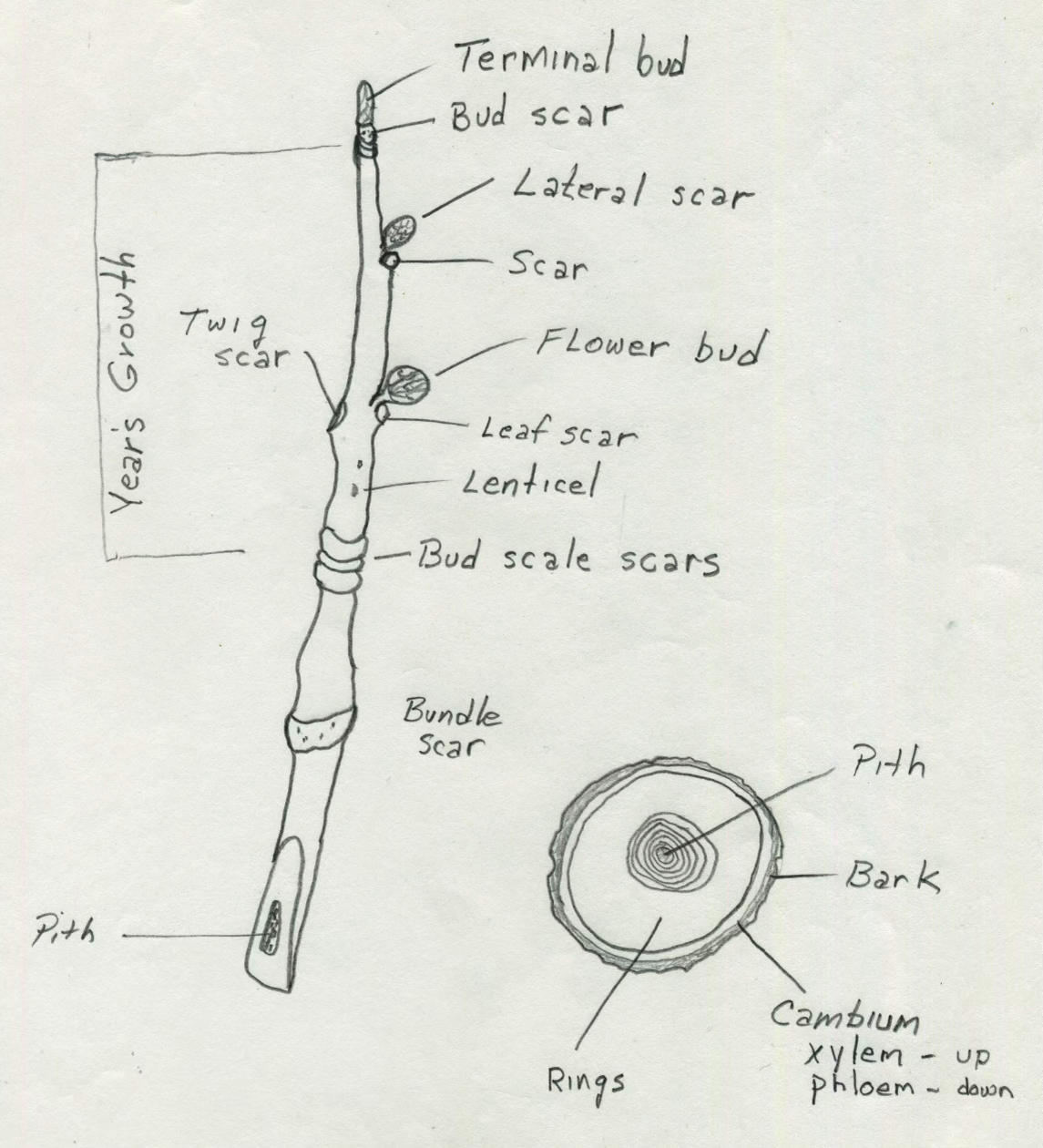

Twig anatomy diagram

Twigs and tree botany

Twigs

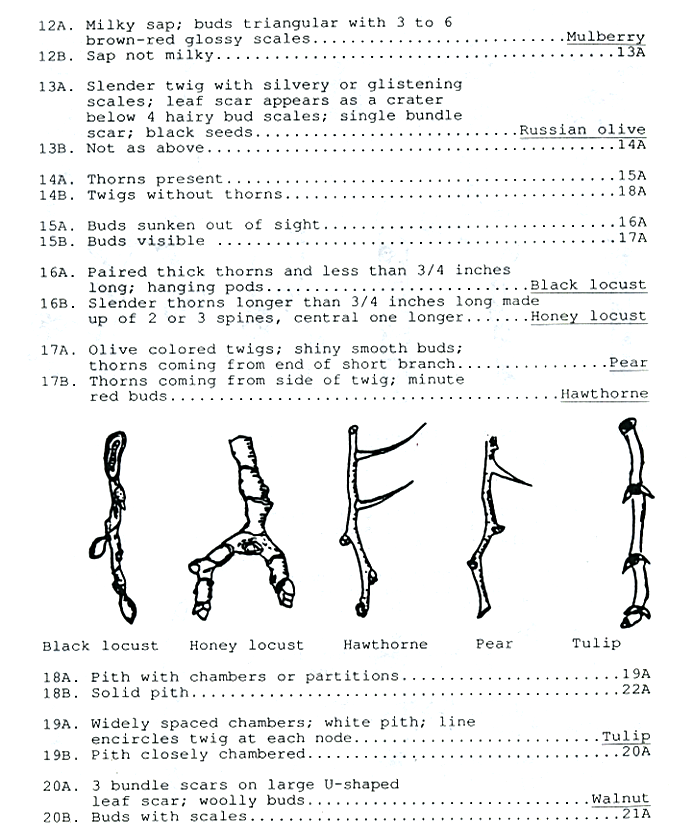

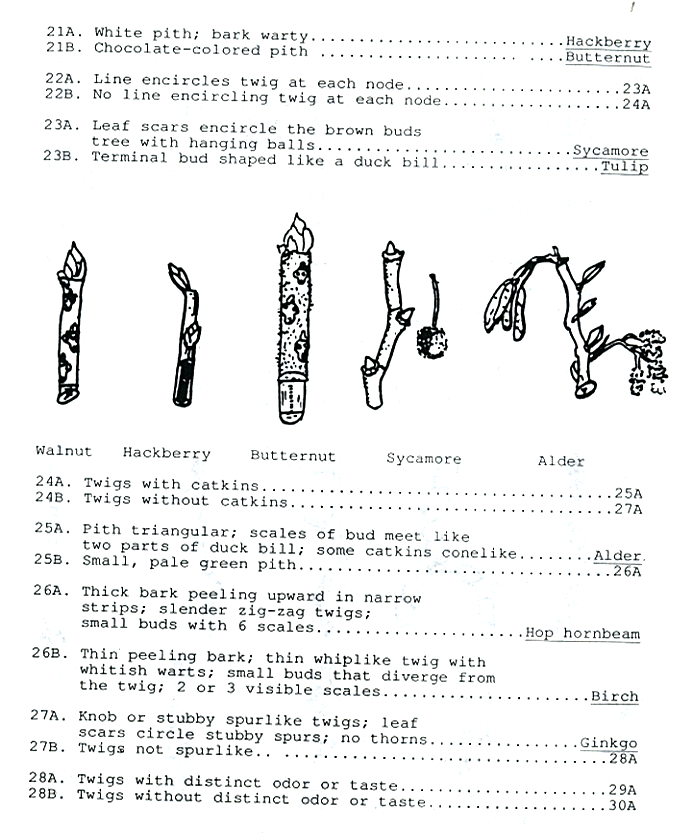

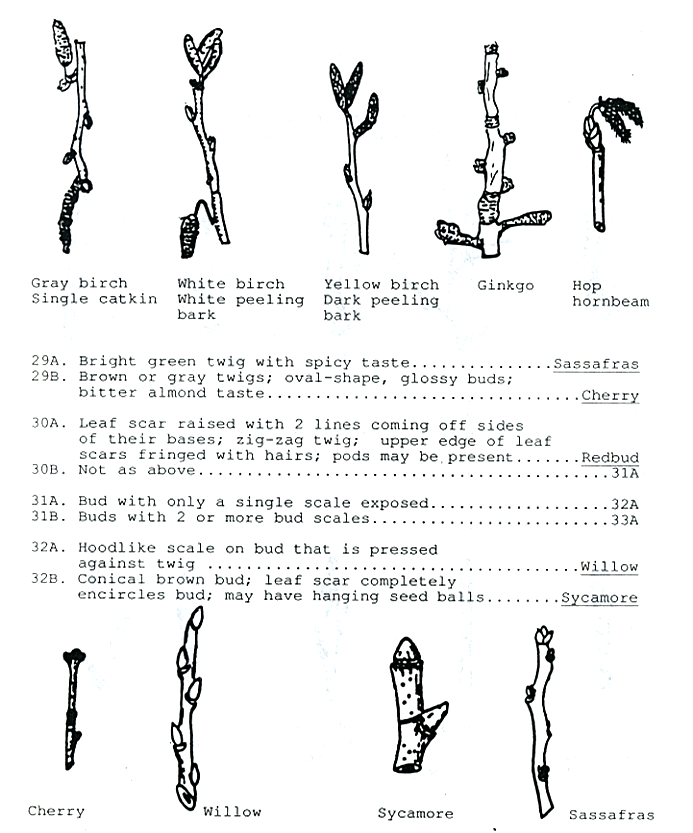

For many of us, when tree leaves fall for the winter, it would seem difficult or impossible to identify trees without their leaves. However tress without leaves still have enough identity to be recognized, however, it takes a bit more study to learn which tree is which from looking at their trunks and twigs.

Before we explore the basics of twig anatomy, let’s review what happens to trees across the seasons.

During the winter the reduced temperature and light slows the tree's ability to grow and produce, yet they are still alive, so when temperatures rise, oxygen goes into their twigs, through tiny pores (lenticels), and respiration increases. The flow of sap provides energy for them to grow, swell, bloom, and grow the flowers and leaves they set in their buds the previous summer.

Buds, especially those on fruit trees, contain flowers. Other buds produce stem growth and leaves. While flower and leaf buds may be found right next to each other on the same twig, they develop from different embryonic cells within the twig.

Leaves produce energy to continue to grow and any surplus is stored.

New buds, for the next year, are formed in the summer from embryonic tissues in the twig which will be the next year's growth. As the days shorten, light decreases, temperature decreases, the leaves fall and production and growth processes are slowed and the trees and it twigs take their winter forms.

Twig's winter forms are discussed as a means of tree identification next.

Winter twig anatomy

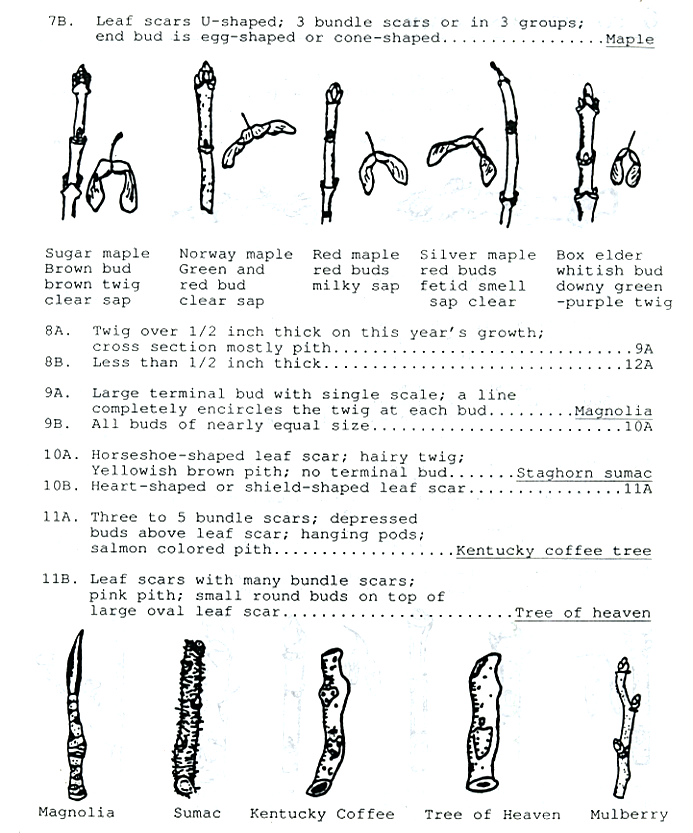

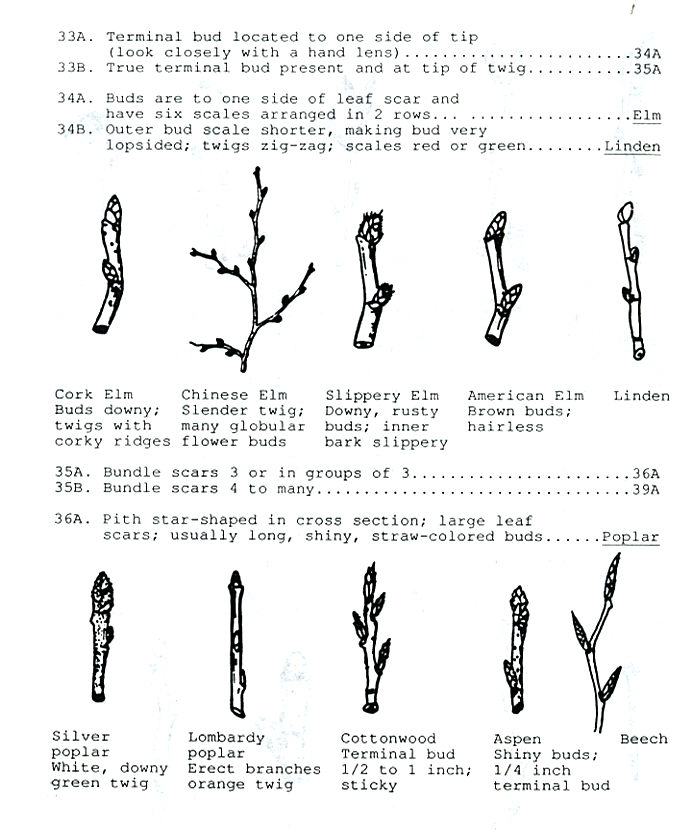

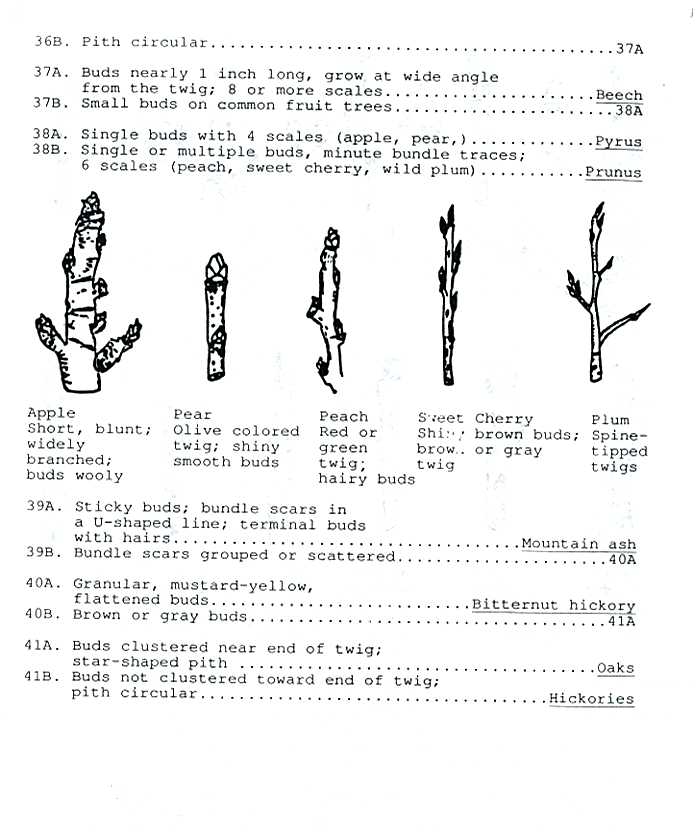

The most noticeable feature in the winter is a terminal bud at the end of each branch. Examination of them and their position can indicate the leaf arrangement, the previous year's growth, and the number of branches that will form in the next growing season.

Let’s review different parts and their functions.

Buds and leaf scars are the most revealing external structures of a woody twig.

Terminal buds are located at the end of the twig. When it is formed, growth ends for the season. Some trees do not have terminal buds. In these trees, the twigs keep growing until their food supply is depleted and then the twigs die back to the last lateral bud.

Lateral buds are located above each leaf scar.

The shape, size, and position of the terminal and lateral buds vary with each tree species. Buds of woody plants are usually protected by several layers of overlapping scales, which are modified leaves, the number and color of which may also be a means for identification.

Leaf scars are on the sides of the twig, they mark the places where the leaf stems were attached. The shape, pattern, and arrangement of the leaf scars varies on different trees. Inside each leaf scar are small fibrovascular bundles or veins. These bundles are the route by which nutrients and water molecules move to the leaf, and the sugars manufactured in the leaf move down to the stem and roots of the tree. Bundle scars are usually quite noticeable and have a definite arrangement and number for each different tree.

Nodes are the places where leaf scars are found on the twig.

- Two leaf scars at a node means there were two leaves in an opposite arrangement.

- Three leaf scars at each node, means there were the leaves in a whorled arrangement.

- If there is only one leaf scar per node, the next leaf scar will occur as an alternate arrangement on the twig.

Internode is the distance between each node.

In the cross section of a twig, the center area is made up of storage cells called the pith. In walnut, tulip, and butternut trees, the pith is divided into sections or chambers; whereas in the cottonwood and chestnut trees, the pith is five-sided, or star-shaped. This observation, along with observation of the buds, leaf scars, and bundle scars, enables us to identify many trees in our environment.

Find out more about trees in the winter in books such as Winter Botany by William Trelease.

Collecting samples

When collecting samples, make sure it is permissible to do so. Then select twigs that are well formed and about 8-10 inches long. Twigs which are located on the tree where they would potentially be pruned in the spring. For example twigs that grow on the underside of a branch or or in the middle of the tree on or close to the trunk.

Attach a masking tape tag to it and label the location and date it was gathered. If known write the common name and scientific name. if not, then leave room for it to be added later.

Select a twig and use the anatomy information to observe and record information and make a sketch and take notes for the following.

Tree - general information - overall structure and shape, have needles or leaves and diagrams

Buds - size, color, shape, terminal bud present

Leaf scars - shape, pattern

Bud arrangement - opposite, alternate, whorled

Other characteristics - twig color, thorns, still attached flower and fruit parts

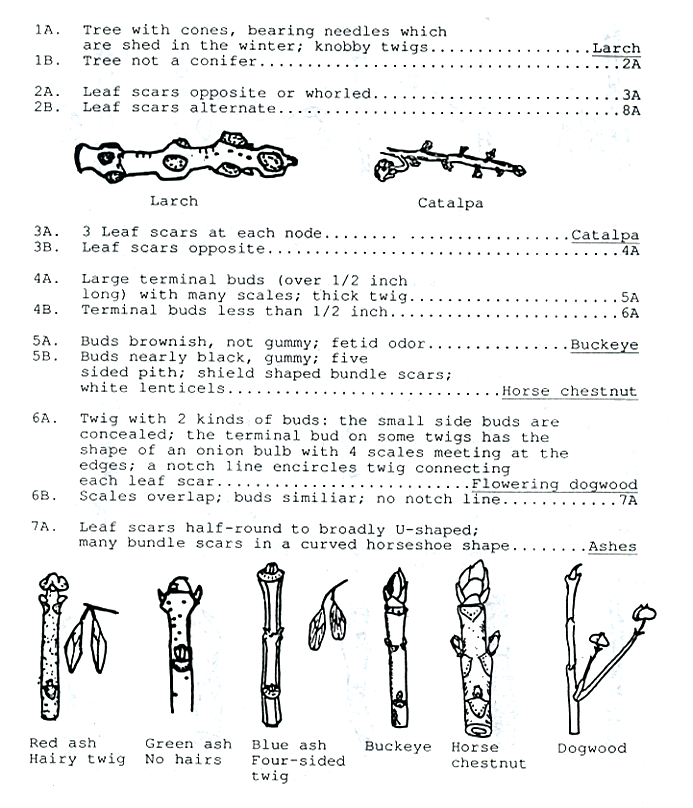

To identify the tree you can use a twig guide similar to the dichotomous leaf guides above. Like the sample below or one in the Winter Botany book or other guide.

Trees & greenhouse gases

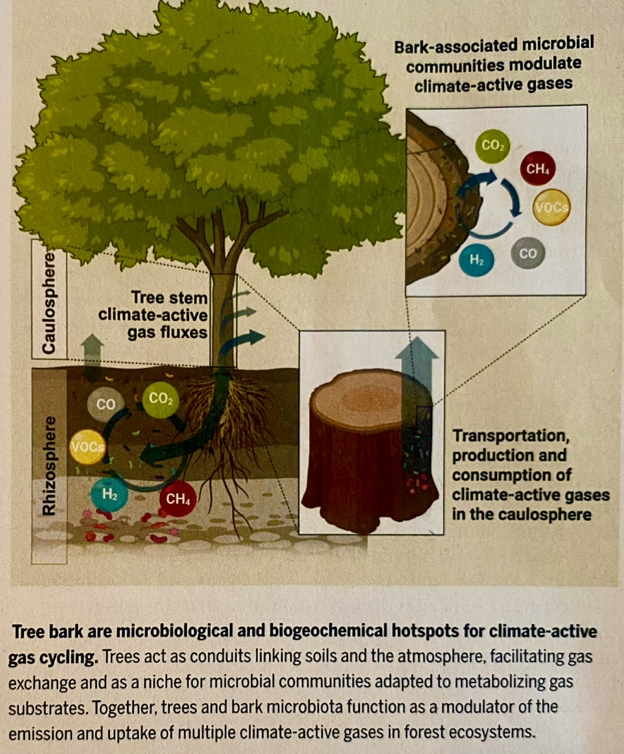

Barrk and microbial communities related to gases

Source

Science. Bark microbiota modulate climate-active gas fluxes in Australian forest. Pok Man Leung. et. al. January 8, 2026.

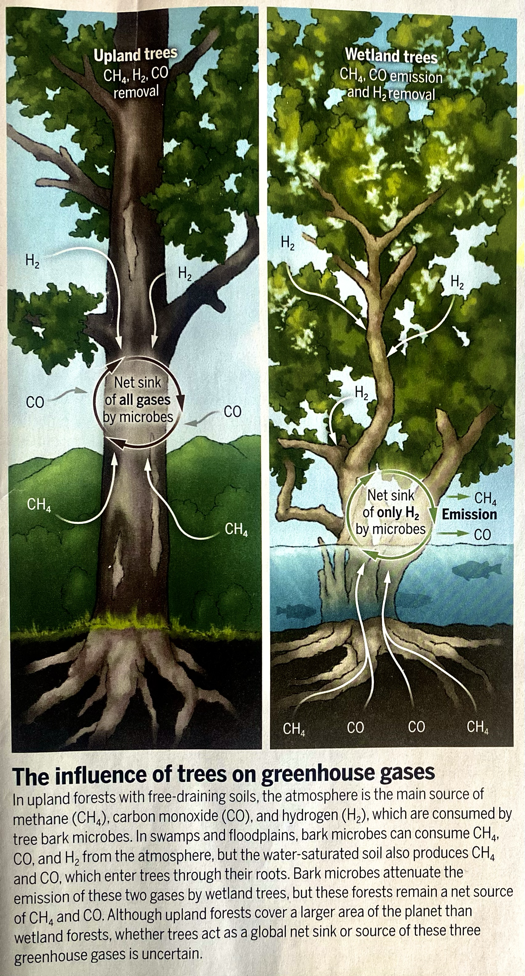

The influence of trees on greenhouse gases

Source

Science. Tree bark microbes for climate management. Vincent Gausi. January 8, 2026.

Deciduous tree twig dichotomous identification guide with drawings

Deciduous tree leaf identification guide with drawings

Want to illustrate your own? Use this identification guide and add illustrations of leaves or make one of your own!

Here you go!

Leaf identification guide Evergreen (conifer)

Want to illustrate your own? Use this identification guide and add illustrations of leaves or make one of your own!