Information to Describe and Become Outstanding Professional Science Educators

Introduction

This article focuses on knowledge necessary for professional science teachers to teach science. A professional educator's educational knowledge base and conceptual framework model includes, information teachers need to know to teach and what students need to know to be educated. It omits specific subject or discipline knowledge and how best to teach that knowledge and leaves it to be delineated elsewhere. The focus here: is to explore the knowledge professional science educator's identify as essential for science literacy, science knowledge base, and how professional science educators facilitate science learning, conceptual framework for science educators.

How to develop as a professional science educators

Three basic things are needed:

- A process for professional science development. A process of continual reflection on our decision making that seeks continued professional development with current research to questions an improve our wisdom of practice to positvely affect our student's development of science literacy.

- A description of science knowledge base necessary for science literacy.

- An science conceptual framework to use to plan and facilitate science literacy.

What process?

A process to inquire and reflect on our science conceptual framework is necessary to make decisions which will best facilitate science literacy. A process that is a reflective cycle, which begins with our present science understandings and educational practices.

Our beliefs, dispositions, assumptions, philosophies, science knowledge, instructional methods, sources of research, and wisdom of practices that are the basis of our goals and how to use ideas to reason on the selection of our plans, practices, and assessment and the consequences of our actions and decision as to their benefits to students.

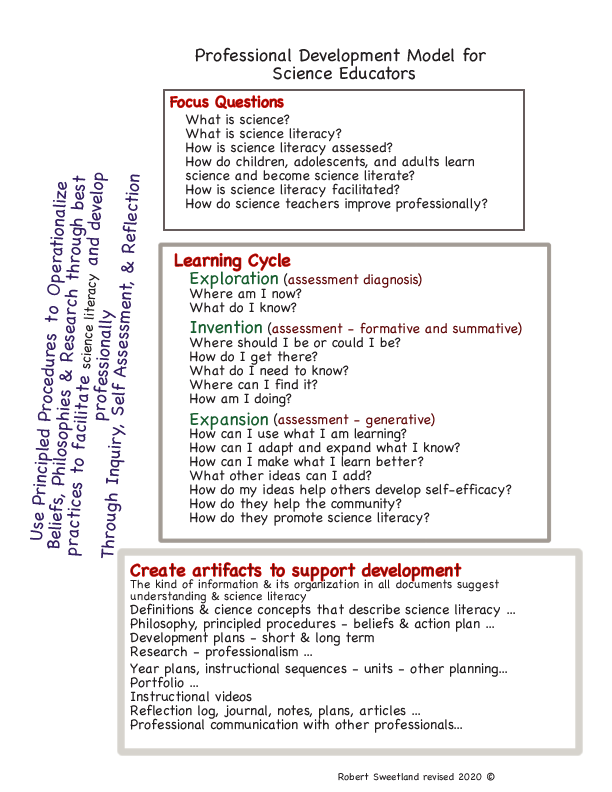

This model suggests how we, educators, use a learning cycle, as a process, to reflect on our practices by asking focus questions to facilitate our professional development.

What do professional educators need to know and be able to do?

There are three kinds of knowledge professional science educators use when making decisions:

- general worldly knowledge;

- general pedagogical knowledge (teaching and learning and the role of education and educators represented in an educator's conceptual framework; and

- specific science knowledge and how it relates to itself, the world, and pedagogical knowledge.

All three are important, our focus here is on the last two: science knowledge and pedagogical knowledge necessary for science educators to facilitate science literacy. Which leads to the focus questions in the professional development model:

- What is science?

- What do people need to know to use science/ be science literate?

- How do I assess what people know about science/ science literacy?

- How do children, adolescents, and adults learn science/ become science literate?

- How do I facilitate peoples understanding of science/ literacy?

- How do I improve my understanding for science and how to help others understanding?

The missing details?

The big ideas represented in these questions are enormous and how we answer them is our professional science conceptual framework. The details and its systematic organization has been described in many publications. Outstanding teachers have this information stored in their memory so they can make decisions on the fly to facilitate science learning. If we don't acknowledge and systematically study and learn about these big ideas, then our decisions will be poorer and students less likely to learn.

Therefore, outstanding science educators construct a comprehensive understanding of pedagogy and science to facilitate science literacy. The amount and quality of information a person has directly relates to the quality and number of choices available for their decision making. Which in turn increases or decreases the likelihood of success for our students and ourselves as educators.

Let's consider what a comprehensive view of science content in a science educators conceptual framework would include ...

Let's start with ...

What is Science?

Many intelligent people have played around with defining science - some of them more seriously than others resulting in a variety of definitions.

I am sure you recognized ideas, within science definitions, you would include in your own personal definition of science and some you would not.

But, you say what is the real definition or the best definition? Well, from that list my favorite is:

A carpenter, a schoolteacher, and scientist were traveling by train through Scotland when they saw a black sheep through the window of the train.

"Aha," said the carpenter with a smile, "I see that Scottish sheep are black."

"Hmm," said the school teacher, "You mean that some Scottish sheep are black."

"No," said the scientist glumly, "All we know is that there is at least one sheep in Scotland, and that at least one side of that one sheep is black."

Awe ... come on you say, that can't be it. Probably not, but it really gets to the heart of science - Observation.

Everything we know, when doing science must be observable and not only observable, but repeatable or verifiable.

Thus, with observation being the basis of science, many philosophers have philosophized about observation: is it real, is it imagined, what makes better observations, and is every person's imagined observation exist only in their mind? ... and so on ... but I will leave these ideas for the interested to explore elsewhere ...

So let's move on ...

Enough ... get to a definition

Alas, there is not one. There are many things that science is and there are many things it is not; the most important that it is not, is anything that isn't based on verifiable observation.

Philosophy based on beliefs and assumptions, religion based on faith, intuition based on a gut feelings, or arguments built on assumptions that we are unwilling to challenge. Conclusions made based on these ideas, are not scientific.

That doesn't devalue those decisions, or put greater value on decisions that are scientific. It is human nature that decides what to value and what process or processes to use to decide what to believe or not. When we choose decisions based on verifiable observation, then science is the discipline that has been created and refined for that kind of decision making.

So what implications does this have for a professional science educator?

Fortunately, or unfortunately, it requires more study. A simple definition of science can be useful to point us in an appropriate direction, but unless that definition includes an in depth understanding of science as investigation, how to investigate, skills necessary for investigation, what has been learned and created by science; and what science can do, when to use it, and when not to; then a definition isn't very helpful for professional educators.

So the solution is to dig deeper, we need to explore ... science literacy.

From science definitions to science literacy

How to tame the powerful question: What is science literacy?

First, a little history:

In 1989 a group of scientists and educators joined together to create a project group and called themselves Project 2061. Their first task was to compile a book, Science for All Americans, a comprehensive description of what science literacy is. Is is and an excellent source for professional educators. This and more of their work is available at the (American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

The information in Science for All Americans, is a compilation created by an expert panel of scientists, mathematicians, social scientist, and technologists of what they believe every American graduate should know and be able to do to be science literate; not what a person needs to know to be a scientist, nor what a student needs to know to be awarded a science scholarship to a prestigious college or university to study in a science field, but what everyone should know. More importantly for you, it is what a professional educator needs to know to teach at any grade level. It is what can be included in a science knowledge base and professional science educators conceptual framework.

Another group the NSTA (National Science Teachers Association) also publishes many professional science documents and most notably the National Science Standards and the Next Generation Science Standards.

Another group The National Research Council (NRC) of the National Academy of Sciences published A Framework for K-12 Science Education in the summer of 2011, which is available at The National Academies Press.

If you want to review one or more of these, head off into the wilderness and take a look:

- AAAS and documents created through the Project 2061 group

- NSTA (National Science Teachers Association) and the National Science Standards

- Next Generation Science Standards

- The National Academies Press and A Framework for K-12 Science Education

- List of links to these documents and others along with summaries and outlines.

Hurry back...

Wow! They each have a lot of information.

Yes, they do, but for now just know these groups have resources, which you are now aware of and can reference it you choose.

So let's continue toward ...

A science knowledge base for science educators

Definitions of science and the ideas in these documents help identify a science knowledge base or the body of science knowledge accumulated by human activity to organize and interpret reality with the use of verifiable evidence to understand the world. What we need to know to teach our students.

A person's science literacy is an individual's ability to use science in the real world.

So to decide what should be in our science knowledge base let's review science content and its categories?

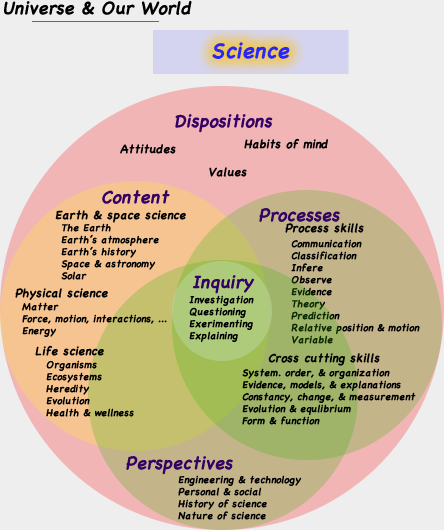

A survey of science information in science documents finds the information can be categorized into the following big categories (dimensions). For example: You can give it a test drive by finding where to categorize these different ideas and skills for science literacy.

- Inquiry

- Processes & cross cutting concepts

- Content

- Dispositions

- Perspectives

- See more on categories in subjects and disciplines.

Represented visually:

Which of these dimensions are represented in the different documents listed above?

Good question. Let's compare them using the four dimensions that all subjects were found to have in a meta analysis of different subjects.

Hopefully, this information will help you see the strengths and weakness in different documents used to represent a science knowledge base.

This collection of concepts and misconceptions can be considered a science knowledge base.

So we now have a process for professional science development and a description of a science knowledge base necessary for science literacy.

So let's look at a professional science educator's conceptual framework, or how to plan and teach science, after a short activity to reduce your anxiety level for teaching all this science.

Anxiety?

Is all the information increasing your anxiety as a science teacher?

If so, try this, and hurry back...

I hope that encourages a desire to review and study a knowledge base or conceptual framework for science educators and our students.

If you have a bit of stress or anxiety, look over this survey (don't worry about comprehensive answers, suggestions are below) about the nature of science.

The nature of science is important, because it is the foundation for science literacy and there are many misconceptions on its nature in the media and the general population. So let's look at the survey again ... Remember? I said I would help you so here are suggestions and misconceptions for each of the questions.

I imagine your thinking on the nature of science questions was pretty deep. The information is pretty comprehensive for an overview of the nature of science, but as a future professional science educator you need a solid understanding of the big ideas of science literacy. Don't worry you can always use these resources.

Before we move to the pedagogy (teaching and learning) in a science educator's conceptual framework, let's review three key ideas for the nature of science and how to use them to answer questions, provide explanation, and reduce your anxiety to facilitate science literacy.

- First, science is based on verifiable observations. This helps to resolve questions by asking: What do we know? What observations are the basis for our understanding? How do our explanations fit the observations? Using the process of science to answer science questions leads to science literacy and science knowledge.

- Second, in science there are no right answers. Science is never done. There certainly are ideas that are more accepted, by the scientific community, than others, but the nature of science is every idea is open to change. Accept this and use it as a strategy with students. Questions don't need to be answered immediately. Asking how can we answer a question can often lead to deeper learning than an immediate answer and model science inquiry and its processes.

- Third, no matter how much science you know it will never be enough. Understanding the world is an infinite task. Asking what we know now may provide answers and if not will provide a starting place to gather more information to continue learning.

So let's move on ...

Continuing toward a professional science educator's conceptual framework

As a professional science educator we have reviewed:

- How do professional educators improve professionally? process for professional educators development

- What is science? nature of science

- What needs to be known to be science literate? science knowledge base

This leaves the pedagogy focused questions:

- How do we assess student's science literacy?

- How do people become science literate?

- How is science literacy facilitated?

Big ideas related to these questions can be illustrated in a Professional Educator's Conceptual Framework of Education or in a professional science educator's conceptual framework. More on this below.

Specifics for how to assess, learn, facilitate science literacy see related topics in the science teacher's tool box.

Bringing it all together

We have a sample model that illustrates a Professional Educator's Conceptual Framework of Education. We could use it and edit it to create one specific for a professional science educator's conceptual framework. The subcategories could reference additional documents that relate to the categories.

For example: How do professional educators improve professionally? Would reference: the diagram for a process for professional educators development and the subcategories for professional development in a document with principled procedures for science educators.

This diagram could be a map for a science educator position paper or science educator professional portfolio.

In addition to the professional educator conceptual framework on education here are two additional samples with some parts and pieces as suggestions:

As suggested the map could start as a planning document and evolve into a map for information in a science educator's position paper, or a professional portfolio. Each, would include other documents to support your abilities: philosophies, principled procedures, lesson plans, units, sequence plans, currriculums, teaching videos, student artifacts, professional assessments, reflections, and more.

Additional professional assessment ideas

As we use a professional development model and learning cycle to assess and evaluate our science practices and development we can go beyond the questions in the model by asking:

- How does our science knowledge base fit with the pedagogical aspects in our professional science educator's conceptual framework?

- Does it fit your educational philosophy?

- Does it suggest current research and wisdom of practice?

- What kinds of learning environments:

- inclusive

- social

- physical

- materials

- safe

- How children learn and develop science literacy

- How to create and implement science curriculum

- What dispositions, or habits of mind are associated with doing science well

- How to assess and kinds of assessment

- How to involve parents, community

- Kind of technology

- Other specific questions and ideas ...

If not what changes would you make to suggest your understandings of these three kinds of knowledge?