Responses to literature and how facilitate growth

The most important response a child can have with a piece of literature is enjoyment. The pleasure a child gets from a story will determine their desire to seek other stories and ultimately if they develop a life long love of literature.

Overview

- Overview

- Introduction

- Model

- Kinds of responses

- Teaching applications

- Developmental responses to literature

- Development of quality responses to literature or characteristics of written journal response levels - use as a resource for critical analysis scoring guides

- Learners' development of story elements by grade level

Overview

To facilitate learning and communication it helps to know the different kinds of responses a person can have with literature and how they change as children grow.

This page discusses the kinds of responses and the development of children to adolescence with respect to literacy and literature.

Responses

Introduction

People seek pleasure from a story, but are limited in their responses by their physical, cognitive, and affective abilities. Abilities, which develop over time and the level of development is facilitated by communication and life experiences they bring to a story. These interact with other variables as they read, view, or listen to literature; creating a unique transaction between them and the story in a literary piece to shape their responses.

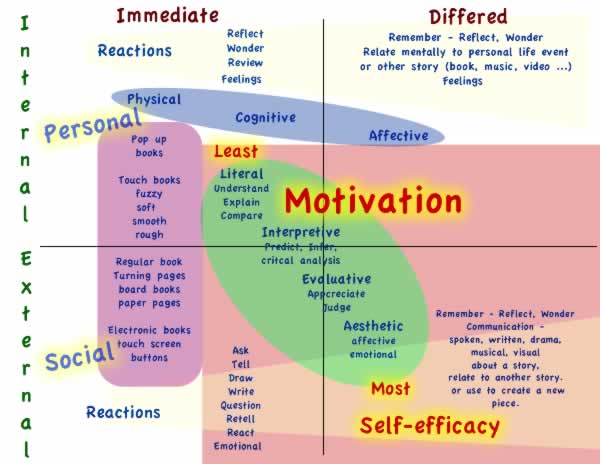

Response may be immediate or deferred; internal or external; emotional, interpretive, or evaluative; and literal, inferential or evaluative as well as at different levels of involvement and understanding.

These responses are illustrated in the following model and described in the text below.

Response model

Kinds of Responses

- Immediate or deferred,

- Internal and personal or external and social,

- Physical, Cognitive or intellectual (literal, interpretive/ inferential, critical analysis/ evaluative), and Aesthetic (affective or emotional)

Immediate and deferred

All responses are immediate or deferred and the timing of a response can vary considerably. An immediate response can be good or problematic as when it interrupts the flow of understanding and involvement. A deferred response, can be good if it is deferred until a discussion starts. Or sometimes it might be even years later when it might be recalled and related to something else. Deferred until another influence sparks a memory, making those responses valuable. However, sometimes the source, as being literature has been forgotten.

Internal and personal or external and social

A person's response to a piece of literature will always include an internal or personal response, this quality is important for creating and sustaining personal involvement with literature. Without it, people stop interacting, and voluntary involvement with literature is halted. The choice to be involved and maintain involvement, usually lead to a positive emotional responses or positive feelings toward literature, which is required to establish a life long love of literature.

As important as the internal and personal response is the external. An external response is required to communicate information about the piece of literature. Examples include: body expressions, oral remarks, written remarks, drawings, diagrams, webs, creative movement, dramatics, play activities, and many other kinds of activities. It is vitally important for educators as it is the only way to communicate about literature and to assess a person's understandings and feelings about a piece of literature. It provides the information needed for teachers to model critical analysis and appreciation of literature to facilitate an individuals and groups better understandings and appreciation of its value. Therefore, it is critical to learn how to encourage students to share their responses socially so they can develop their self-efficacy to enjoy literature at their choosing alone or with peers.

Physical, Cognitive, Aesthetic

These responses are related to different ways literature is experienced. While a literate adult may wonder about the inclusion of physical it is most likely the physical responses young children enjoy that encourages them to continue to seek literature for enjoyment.

Physical

- Touching and feeling texture of the page and other textures in feely books

- Pointing

- Turning a page or not wanting to turn the page

- Hearing interesting sounds: alliteration, rhyming, rhythm...

- Seeing bright colors, interesting objects, animals, people, vehicles...

- Verbal and non-verbal responses based on physical sensations.

- Experiencing the unexpected.

Cognitive or intellectual (literal, interpretive/ inferential, critical analysis/ evaluative)

The response made after mentally manipulating the information from the story and communicated can be classified as literal; interpretive/ inferential, critical analysis; and evaluative. All of these response may also be immediate, deferred, internal, external, or aesthetic/ emotional.

Literal

Responses that can be supported directly with evidence from the text, pictures, illustrations, charts, diagrams, music, sound, or action without making an inference.

Interpretive or inferential

Interpretive or inferential responses: Are interpretations that go beyond the specific information provided by the author or illustrator. The reader/ listener/ viewer interpret words, visuals, or sounds singularly and in combinations using his or her experiences to interpret beyond the literal meaning of the story. He or she make inferences about the story and the author's motives usually by reacting to the elements: plot, setting, style, mood, point of view, tone, and the genre attributes of the work. While these responses are interpretive or inferential they are also supported with evidence.

- That character is really evil, because to do ..... you would have to not care about people or other living things and get enjoyment at the expense of others...

- This story isn't true, is it?

- I don't think Camazots is on Earth. In fact it's not in the solar system and maybe not even in our galaxy, because the author's description of the planet would not match anything we know about our solar system. While it might be in our galaxy it don't think it is because of the the tessellation thing.

Critical analysis and evaluative

Evaluative responses: an example is when the reader/listener/viewer selects an example or multiple examples and explains why they think the author did ... or what the author should have done based on a standard. If a child says the book is one of the best s/he have ever read and tells why, compared to another piece of literature or a standard, she is giving an evaluative response. If a child says that a character should do something. You wouldn't know if it was an evaluative response unless it's explained in relation to a standard. The standard for being aesthetically beautiful is what we we call art.

- I liked it when the author said the wheat fields looked like his brother after a buzz cut.

- This book is boring because there is not enough action.

- I liked the way the author describes everything that makes you feel like you are there.

- She makes it seem so real. Like when she said Jess's muscles were popping like bacon on a griddle and by what she had Jess talk to himself when he was trying to run away after he was told Leslie ...

- A person asks if there are more books like the one(s) she or he just read and describes what they mean by just like.

- A person's reaction to a song, video, advertisement, movie explaining what they liked and why.

Aesthetic (affective or emotional)

People who are involved emotionally comprehend and evaluate their reading/viewing/listening better than those who aren't. Therefore, if we know what the reader/listener/viewer's responses are we can anticipate his or her emotional reactions and interact to facilitate his or her growth.

- "I can feel the frustration!"

- "That character reminds me of when I..."

- "I would like to live in that place."

- "I would not like to have lived during that time."

- "I would like to know that character."

- "This reminds me of ..."

- A child smiles and giggles after reciting a poem and repeats a few rhythmic lines over and over.

Teaching applications

Personal involvement is required to create meaningful responses and to communicate those responses externally. It is the external responses which are evaluated by others which may result in others desire to increase their involvement with the same literature or to share their personal responses as a result of their interactions with others. It is listening to learners or looking at the artifacts they create that we can gather information to make decisions to offer readers choices to facilitate their literacy by helping them to respond with increased understanding: literal, interpretive, or critical analysis to evaluate and appreciation literature.

Responses and interactions which can be complex and wide ranged as illustrated in the responses model.

It is important for educators to celebrate and encourage learner involvement with literature. The best time to facilitate better understanding, enjoyment, and appreciation of literature is when learners communicate their response from their personal transaction.

Teachers make and take advantage of these through the questioning strategies they use to encourage and scaffold deeper thinking through critical analysis. As learners achieve higher quality responses they will also develop a greater appreciation of literature and desire to communicate with others to share their transactions and ideas. As they have more experiences with quality literature and outstanding teachers their responses can improve from novice to emerging, to mature, to critical responses as described by the outcomes on this scoring guide. Additionally as students are introduced to story elements and genre they will also develop their abilities to use these ideas to understand, interpret, analyze and appreciate literature.

To better understand and predict students' responses to literature and how to anticipate how they might development it is interesting to consider different developmental theories and how they might be applied to facilitating literacy as learners develop from childhood to adolescence.

Development of responses to literature from child to adolescence

Responses improve with cognitive and affective growth and development. Let' explore some.

A child's first response to literature is usually a physical touch or grab.

The first response an adult hopes for is - a request for more.

A child's development to tell stories begins with a response of retelling a story beginning with a restatement of words, then phrases, and eventually a literal retelling of the story. All of these responses can be sprinkled with short interpretive responses (laughter, smile, or descriptive words or phrases).

Later interpretive responses are added to the retelling narration (when I was..., I had a dog that...) where children interpret the story and relate it to similar personal experiences they have had. With practice the responses become a more comprehensive personal retelling of the story with emotional, interpretive, and evaluative responses.

In the elementary school these emotional and interpretive responses are critical as they allow readers to enter into a story and make it their own. Resulting in better evaluative responses through increased comprehension (literal, inference, critical analysis, and evaluation), and appreciation.

Expression of ideas: Small children have problems stating themes of stories. We should realize, however, that although a small child cannot define "home" or "mother" they know what the concept is. Security, love, comfort, warmth, protection, honesty, are abstractions they may know but are unable to articulate. For children, knowing and saying are rarely the same.

Vocabulary: The better the reader's / listener's / watcher's understanding of vocabulary used in the literature and to describe literature pieces the more significant the involvement and the better they are able to communicate a response. Therefore, discussing and developing vocabulary is essential. However, we need to be careful to do it well and not make it dull or drudgery. Suggestion and additional information for developing vocabulary.

Attention span: The better the reader's / listener's / watcher's attention span is maintained during the story the greater the involvement.

Amount of digression: Increased digression in the literary piece decreases involvement.

Relationships of character and actions:

- Young children are limited in their awareness of alternatives.

- Young children can be prevented by their elders from making discoveries on their own and developing alternatives when they are told what to do or have things done for them. We must give all students freedom to analyze and explore possibilities, but also guide their discoveries when necessary by modeling critical thinking and aesthetic valuing.

- Children rarely see motives for behavior beyond what they would like to see. We must encourage them to probe deeper and when necessary model how to do so.

- Children see choices as black and white, they are unaware of their own mixed motives, and rarely see those of others. We must encourage them to probe deeper and when necessary model how to do so.

Social character development Social skills and understanding is learned through interactions with people. Children with limited social experiences are not be able to understand social character development. However, if a story is within their zone of proximal development (ZPD) they can with support.

Amount of action and order of action: Students' memories are limited in the number of events they can remember that occur at the same time. Even adults are limited to about seven ideas at a time. Students can remember more if the ideas are told sequentially and chained together in some manner. Flashbacks are confusing to children who have not developed a fairly sophisticated concept of time (remember your first experience with them?).

Children are more literal than adults: Fred Gwyn'e Moose, Amelia Badelia are examples of what students enjoy about second grade when they begin to understand beyond strict literal interpretations.

Learners' development of story elements by grade level

| Story Element | Kindergarten | 1-2 grade | 3-4 grade | 5-6 grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characters |

|

|

|

|

| Plot |

|

|

|

|

| Setting |

|

|

|

|

| Theme |

|

|

|

|

| Point of View |

|

|

|

|

| Style |

|

|

|

|

| Tone |

|

|

|

|

Using developmental theories to predict and understand children's responses to literature

Understanding what and how children think can help us understand how they respond to literature. Therefore, theories of child development that suggest how children grow and develop socially, intellectually, morally, and physically can help us understand how they think, what their interests are, and their different needs across different ages. Information to help guide your selections and to guide their selection of literature.

Six developmental theories, on children's growth through childhood and adolescence to adulthood, related to examples of children's literature that correspond to the developmental characteristics.

- Erikson's Theory of Psychosocial Development

- Kohlberg's Theory of Moral Development

- Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

- Piaget's Theory of Development

- Social Learning Theory

- Caring responses

Development of Quality Responses to Literature or

Characteristics of Written Journal Response Levels

Novice Responses includes - |

|

Emerging Responses includes - |

|

Maturing Responses include - |

|

Critical Responses include - |

|

Resources

- Using developmental theories to predict & understand children's responses to literature

- Literacy & literature curriculum development and planning - for more tools

Home: Literacy, media, literature, children's literature, & language arts